The Expansion of Legalized Marijuana

Overview

Like it or not, the states and the District of Columbia are changing the course of national drug control policy. The liberalization of marijuana laws has occurred at a pace that exceeds available knowledge of how best to manage the new industry in a way that promotes public health and safety. Motivated by the public’s perception that marijuana is medicine and that the war on drugs has failed, policy experts must now turn to closing the knowledge gap so that implementation of new marijuana laws is better informed by research and science. This policy brief identifies some of the key knowledge gaps that must be addressed to ensure that the liberalization of marijuana laws and the regulation of this new industry occurs in an evidence-based environment driven by research and facts and not by anecdotes and beliefs.

Background

While marijuana remains illegal under federal law and continues to be classified as a Schedule I drug (meaning it has a high risk for abuse and has no accepted medical value), many states and the District of Columbia disagree. Fifty-five percent of Americans now reside in states that have medical or full legalized use. Five additional states may legalize marijuana for recreational use on Election Day (Arizona, California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada) and three other states are considering permitting marijuana use for medical purposes (Arkansas, Florida, and North Dakota).1 If these initiatives are successful, 63 percent of Americans will reside in states that have medical, full legalization, or both types of use. In light of this extraordinary movement, and the fact that the majority of states have some form of marijuana liberalization, it now seems that being on either side of the issue is moot. Government at all levels must instead turn its attention to being proactive rather than reactive by adopting a systems approach to regulating this new industry and designing programs and policies that protect the public health and safety. This policy brief does not address the wisdom of marijuana legalization, but instead asks two important questions: 1) If legalization is coming, how best should marijuana be regulated? 2) What research questions need to be explored so that science can catch up with this dramatic shift in public policy?

How did we get here?

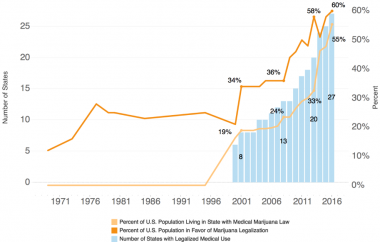

Public opinion favoring some form of marijuana legalization has shifted dramatically in two decades. In 1996, when California led the nation in legalizing marijuana for medical use, less than 15 percent of the population supported any type of liberalization of marijuana laws (see Figure 1). In 2016, 26 states and the District of Columbia (the states) have medicalized marijuana, and five of these states also permit marijuana use for recreational use.2 Also in 2016, 20 years after California medicalized marijuana, 60 percent of the public supports some level of legalization.3 There seems to be two beliefs driving changing public opinion. One driver is the belief that that the so-called war on drugs has failed.4 Instead of reducing drug use, many people believe it has only succeeded in creating high rates of incarceration of citizens for drug possession. The second driver may be the public’s belief that marijuana has medicinal value. As Figure 1 shows, the passage of laws permitting the use of marijuana for medical purposes is very highly aligned with changing public opinion favoring legalization. Of course, this correlation could be mere coincidence, as it is not possible to attribute a causal relationship between these trends without further study. Each of the five states considering recreational use of marijuana on Election Day has already legalized the use of medical marijuana. If the passage of laws permitting medical use is a precursor of recreational use, the likelihood that more states will move to permit recreational marijuana use is strong. Liberalization of marijuana laws among the states moves the task of regulating this new industry to the forefront of the policy agenda.

Trends in Public Opinion and Population Access to Legalized Marijuana

Systematically Regulating Marijuana Markets

All states that have legalized marijuana so far have used a commercial and competitive, but regulated market structure. This allows cultivation, production, and sale in the private for-profit sector—modeled after the alcohol industry. With the likelihood that voters on Election Day will expand the number of states permitting recreational or medical marijuana use, state policymakers must address how best to regulate, monitor, and assess the performance of their oversight system to fine tune its performance. Marijuana regulations cut across many areas, including health, public safety, agriculture, environment, revenue collection, parks and recreation, education, consumption. and workplace rules. Authorities must define a set of objectives aligned with the public’s desire for reform and federal instructions to ensure non-interference, assuming future administrations maintain current policies.5 A recent study exploring how to regulate marijuana in California recommended that any state considering legalizing marijuana for medical or recreational purpose should develop a single highly regulated market for marijuana.6

The challenge facing these states is implementing regulations that reconcile important but somewhat competing policy goals: limiting the impact of the illegal market, preventing youth drug use, reducing harm to public health and safety, preventing diversion of legal marijuana into illegal markets, and raising revenue. Addressing these goals requires a comprehensive regulatory approach that would tightly document and control the cultivation, production, processing, and sale of legal marijuana. That system would entail at least five broad regulatory areas:

- Cultivation, production, and processing—This area focuses on turning marijuana plants into finished products, including licensing and related regulation.

- Sale, consumption, and possession—This area concerns how the state should regulate consumer use.

- Taxes and finance—How should marijuana be taxed? Will taxes be based on price, weight, potency, or other factors? How will taxes be collected? Should revenues be earmarked to pay for regulation, research, and public health and safety costs?

- Public health and safety— Based on chosen goals, how can a state minimize harm to society—including harm to users through abuse and, for example, harm to others from drugged driving.

- Governance—What is the role of state government? How can performance assessment and research guide policy? How will states promote public health?

Answering each of these questions requires a substantial body of knowledge about the marijuana market. Currently, much of it is undeveloped. States that have engaged in legalization are in uncharted waters regarding how to implement an effective regulatory regime that is known to address public health and safety concerns. As one state regulator opined, “right now, science is lagging policy.” 7 Mindful of this belief, we now turn to questions about the knowledge gap that needs to be closed to align science with policy.

Closing the Knowledge Gap

Legalizing recreational marijuana is a far-reaching policy change. There is little research available on its potential effects on usage rates or public health and safety.8 This section highlights what government—state and federal— should do to close the knowledge gap. The first priority is for data collection, performance monitoring, and analysis. States' regulatory structures should incorporate a feedback mechanism to track key performance metrics and conduct descriptive analyses of the operations of the market and its regulatory oversight system. The second priority is for a sophisticated research agenda to explore the impact of legalization, including a focus on intended and unintended results of policy. The legal marijuana industry is new and a broad understanding of its functional dynamics are mostly unknown. Research can provide state policy and program managers the answer to a number of questions, such as:

- What model regulations should states adopt?

- What is the capacity of the nation’s health care system to accommodate what will likely be an increase in demand, both short-term and long-term, for acute and chronic health care services?

- How will increased demand for health care manifest itself?

- How does substance use prevention reduce first-time use or escalation of use among youth who will witness greater availability and access to what is still an illegal product at the federal level and an illegal product for youth in the states?

- Should the marketing of marijuana be permitted? If so, how and to what extent?

- How does marijuana use relate to other drug use—e.g., is it a substitute or complement to alcohol use? Opioid use?

- What are safe levels of use of pesticides and fertilizers as well as safe levels of mold?

- What is the environmental impact of legalization?

- How do we test for marijuana use and what constitutes impairment?

- How does marijuana use affect driving, workplace performance, and academic achievement?

- How do new marijuana delivery systems (e.g., vaping) affect health and do they have other damaging consequences? What are the health effects of second hand smoke?

- What is the impact of legalized marijuana on illegal markets? What is the impact on grey markets, where legal home grows of marijuana leak or are diverted into illegal markets?

- What is the impact of the new marijuana industry on states’ gross domestic products?

- How does the legalization of marijuana affect the social cost of illicit drug use?

Recommendation

These are just a few of the questions that must be addressed by both the federal and state governments. Marijuana is illegal at the federal level, but that does not absolve it from its responsibility for protecting public health and promoting safety. To address the research questions identified above, the appropriate federal agencies should take responsibility for developing research agendas that fall under their purview (e.g. the Department of Agriculture could address pesticides, AHRQ/ SAMHSA could address healthcare system capacity, and NIH/ NIDA on public health impacts). The nation’s lead for national drug control policy—the Office of National Drug Control Policy—can use its statutory authority to function as a convener to ensure proper communication and seamless integration of efforts between agencies and address these and other topics of interest to drug policy experts and program managers.

End Notes

- Montana also has a ballot initiative related to medical marijuana. However, this initiative would clarify the state’s existing regulatory structure and medical marijuana was legalized in 2004.

- See the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws for detailed summaries of the state law with regard to medical and recreational use of marijuana. http://www.namsdl.org

- Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/196550/support-legal-marijuana.aspx

- One poll reports that over 80 percent of Americans believe the U.S in not winning the war on drugs.

- Although the CSA’s prohibition remains in force, the Obama administration’s Justice Department has issued memoranda characterizing enforcement of federal marijuana prohibitions as low priority—first for the medical market and then more broadly (Ogden, 2009; Cole, 2013). This occurred four years after the U.S. Department of Justice issued guidance regarding non-interference with the medical market (Ogden, 2009). So, under those memoranda, the federal government will not devote resources to enforcing federal marijuana laws.

- Murphy, P. and Carnevale, J., 2016. Regulating Marijuana in California. Public Policy Institute of California.

- Lewis Koski, Deputy Senior Director of the Colorado Department of Revenue. Remarks during the press release of the PPIC Report, Regulating Marijuana in California.

- Caulkins, J., Hawkens, A., Kilmer, B., & Kleiman, M. (2012). Marijuana legalization: What everyone needs to know (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.